|

The forgotten sacrifice of the Irish regiments. |

|

The Greening of the Khaki

Among these men were Catholics and Protestants, fighting side by side against a common foe. Those who were Catholic, and wore the khaki uniform of the British army, have often been considered by Republicans as anglicised Irishmen, traitors to their country, and being more British than the British themselves.

Among these men were Catholics and Protestants, fighting side by side against a common foe. Those who were Catholic, and wore the khaki uniform of the British army, have often been considered by Republicans as anglicised Irishmen, traitors to their country, and being more British than the British themselves.

Not true.

These men were as patriotically Irish as any Republican and fought for Irish freedom more bravely than those who foolishly died in a vain and stupid effort to free Ireland through bloody revolution.

There is no doubt that Catholic Ireland had suffered under British rule. There were the Penal Laws, the unnecessary starvation of the famine, the Evictions, the Property Laws and a range of other devices placed against their progress. Under O’Connell and Parnell to win their freedom by political means, and by 1913 the Nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond was a major force within Westminster. The Liberal government was obliged to listen to their counsel and the possibility of freedom through a “Home Rule Act” had almost come to fruition, despite the opposition of the Protestant minority inhabiting the north of the country.

And yet, despite all the anti-Catholic laws and actions, and the constant delays to the formation of an Irish Parliament, Irishmen flocked to the army as volunteers after the outbreak of war in August 1914. Why?

The answer can be found in the life, which the average Irish Catholic worker lined in Ireland. To find the answer we must therefore consider his social, economic, political and religious background. These areas define the lifestyle a person lives, and a combination of these areas has a direct bearing on the decisions that a person makes.

Huge Gap in Wealth and Lifestyle

In general the average Irish Catholic labourer made up the bulk of those Irish soldiers who fought in the trenches of the Great War. With regard to the strata of society occupied by such men, it was definitely of the lower variety. They had their world shaped and controlled by events dominated by those in the social strata above them. These upper classes strove to maintain the “status quo” in society, within which a huge gap in wealth and lifestyle separated the groups. Just like society in Britain as a whole there was a deep gulf between the working classes and the rest of society, and this was an accepted fact of life. However, unlike Britain, Ireland was not industrialised to any great extent and people’s attitudes tended to be more parochial. In simple terms there was no united and militant working class to stand for the improvement of the worker’s lot.

In Ireland before the Great War the labouring class made up the bulk of those who were unemployed or, at least under-employed. Generally they lived dangerously close to total poverty, earning well below the average wage in Britain, and made no financial contribution to the government’s coffers by way of tax. In squalid, over populated and cramped communities among the narrow streets of Ireland’s towns and cities these people were further handicapped by illiteracy or, at best, semi-literacy.

For such people there was very little if any prospect of being able to drag themselves out of this lifestyle and satisfy any social or economic aspirations that they may have held. In their case there was a definite lack of opportunity to improve their social status, or that of their children.

Ignorance, poverty and lack of hope led to an apathy among the Irish working classes. To help relieve their condition many turned to alcohol and other vices, much to the despair of the clergy, who were concerned about the unemployment situation, though not enough to wish to disturb the existing social “status quo,” of which they were an integral part. There was, of course, the old cure of emigration and this was officially encouraged by local and national leadership In Ireland many took up the opportunity to emigrate to other lands, where many prospered, though many more did not fare so well.

Hard Existence

Those who remained in Ireland continued to face a hard existence, ever striving to avoid the constant presence of pauperism. Despite their poverty the respectable Irish working class would do anything necessary to avoid falling into that abyss. Paupers at this time were obliged to live under the charity of the wealthier classes, forming a group of third-class citizens without dignity and deprived of even their most basic rights.

Those who remained in Ireland continued to face a hard existence, ever striving to avoid the constant presence of pauperism. Despite their poverty the respectable Irish working class would do anything necessary to avoid falling into that abyss. Paupers at this time were obliged to live under the charity of the wealthier classes, forming a group of third-class citizens without dignity and deprived of even their most basic rights.

For many working class men the prospect of their families falling into the trap of pauperism was enough to encourage them to enlist in the army and benefit from its regular pay and allowances.

Within the cities and towns of Ireland the working classes generally lived a cluttered existence. Usually each family rented a room in the small, dilapidated houses, squeezed together in a maze of narrow streets, lanes and entries. And yet, these communities were close-knit, static groups of people in which good neighbourliness and friendships were forged and grew strong.

As today, in Ireland, religion and politics go hand in hand and are not easily separated. Prior to the Great War, just as much as the present day, the political divisions in Ireland followed closely the religious divide. Many in Ireland claim Irish Nationalism to be the emblem of the Catholics, and that this has affected the social and political behaviour of Catholics over the last two hundred years. However, in the years prior to 1914, the attitudes of the Catholic working class combined with the existing class structures to make a potent political mix within the government of the United Kingdom. It was a political mix that the middle and upper class Catholics wanted to harness for their own aggrandisement.

The upper and middle class within Irish Society shared a dominant status and controlled both political and economic power in the land. The nationalist politicians focussed their attention on the perceived differences between the average Irish worker and the British. By clever oratorical skills they obscured the aspects of common heritage between these two groups, while disguising the social and economic gaps between themselves and their audiences.

Proud Part of the British Empire

Admittedly very few Irish Catholics were not fooled by such propaganda. These people were proud to be a part of the British Empire and were very willing to defend it when the call came in 1914. In fact some prominent nationalist politicians were somewhat honoured by the apparently honoured place held by Ireland within the British Empire.

Admittedly very few Irish Catholics were not fooled by such propaganda. These people were proud to be a part of the British Empire and were very willing to defend it when the call came in 1914. In fact some prominent nationalist politicians were somewhat honoured by the apparently honoured place held by Ireland within the British Empire.

Nevertheless, service within the British Army still aroused latent conflicts within the minds of many Catholic Irishmen at this time. The attitude of those Irish men, who had already donned the uniform of the British Army were far from simple, whatever the reasons behind their enlistment. They could quite happily celebrate the efforts of those fellow countrymen who had fought in the various wars of the British Empire, but they could just as easily denounce the British army as an occupying force of tyrannical power.

One well-known Irishman who fought in the Great War, John Lucy, accurately recorded the conflict he had felt when he had enlisted in the army. Though he would have preferred to pledge himself to serve the cause of Ireland, he felt honour bound to Britain by his oath as a soldier. He undoubtedly would have wished that Britain had treated Ireland much better in the past, but he felt no less Irish or catholic because of his enlistment. In fact it appears that, overall, nationalist disapproval of the British army carried little force with those Irish men who were already serving in the pre-war army. Such men were usually poor, apolitical and had joined the army as a matter of practicality rather than political ideology. These men cared little for either nationalism or imperialism, and they saw the army solely as a practical way out of their poverty stricken lifestyle.

Mobilisation in August 1914 saw British and Irish regular troops stationed in Ireland being sent to the front. British territorials, who were charged with the home defence of Ireland, subsequently replaced these men. During the years prior to the war the use of militia and volunteers to create a special reserve in Britain to support the regular army, and the formation of territorial force for home defence, was not extended to Ireland. The powers that be within the War Office did not trust the Irish with their own home defence and thus delayed any decision until it was too late. Thus, when war came and Irish men were needed to fill the ranks, community leaders, clergy and politicians, were recruited to lead the recruitment campaign.

The Persuave Voice of the Clergy

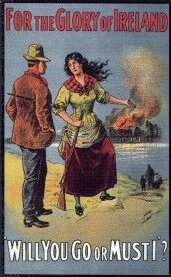

The Catholic religion was central in the lives of the majority of Irishmen in the first half of the twentieth century and, as such was their standing within the community that their views had a significant impact on the attitudes of the devout and practising Catholics, whose faith was also exploited for recruitment and propaganda purposes. Calls to action in defence of “Poor Little Catholic Belgium” being just one effort to obtain the sympathy of the working class Irish Catholic. (PICTURE RIGHT: Irish poster, with Belgium burning in the background)

The Catholic religion was central in the lives of the majority of Irishmen in the first half of the twentieth century and, as such was their standing within the community that their views had a significant impact on the attitudes of the devout and practising Catholics, whose faith was also exploited for recruitment and propaganda purposes. Calls to action in defence of “Poor Little Catholic Belgium” being just one effort to obtain the sympathy of the working class Irish Catholic. (PICTURE RIGHT: Irish poster, with Belgium burning in the background)

The religious role and status of the priests made these men social leaders and the ordinary working class Catholics were almost in awe of them. The labourer’s lack of sound education obliged them to depend upon their priests in various practical matters and gave them almost a mystical aura to their parishioners.

In response many priests developed a paternal attitude towards the lower classes, who were expected to show due respect by doffing their caps or covering their heads. This status, which was accorded to priests, was important in the conditioning of the Irish working class to enlist in the army when war was declared.

To the persuasive voices of the clergy were added the equally persuasive voices of the nationalist politicians, eager to exploit the deeply held nationalist sympathies of the working class Irish. Nationalism served to make the community a more homogenous unit and strengthen common loyalties. Most importantly it also encouraged a powerful loyalty to the constitutionalist cause espoused by the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, John Redmond M.P. Such was the potency of this loyalty at the time of the outbreak of war that it overrode any interests that would encourage them against enlistment after Redmond’s call to arms.

The spread of militant Trade Unionism through Britain prior to the war had little effect in Ireland. It represented only a small fraction of the unskilled Irish labourers, who made up a large proportion of Irish society. Moreover, the Trade Union movement was perceived as being a major threat to the existing social order in Ireland and, therefore, invoked a large amount of hostility among the middle and upper classes. The Catholic clergy, in particular, could not voice support for a political programme, which refused them the traditional status of mediator between the classes.

As a result of all this, on the eve of the First World War, Irish labour was much more docile than its counterpart in Britain. Catholic Ireland was almost a one party state with Redmond’s IPP exercising its monopoly of political power to stifle any diversity there might be in political expression.

Redmond's Call to Arms

Confidently, on 3rd August 1914, John Redmond (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT) told the House of Commons in London that British troops could safely be removed from Ireland, which would be defended by “her own sons”. On 16th September newspapers in Ireland published his call to arms and, four days later, at Woodenbridge he told a mass gathering of followers to “account for yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends.”

Confidently, on 3rd August 1914, John Redmond (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT) told the House of Commons in London that British troops could safely be removed from Ireland, which would be defended by “her own sons”. On 16th September newspapers in Ireland published his call to arms and, four days later, at Woodenbridge he told a mass gathering of followers to “account for yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends.”

Subsequently, at the Dublin Mansion House, on 26th September, Redmond publicly supported Prime Minister Asquith’s call for Army recruits and he asked that an “Irish Brigade” be formed as part of the Expeditionary Force fighting abroad. Despite the political deadlock over the amendment to the “Home Rule Bill” proposed by the House of Lord’s, which called for the permanent exclusion of six northern counties, Redmond’s prestige and personal influence was at its peak among the nationalist working class. To these unskilled men the army’s pay and allowances system was a definite attraction.

Whereas skilled soldiers could earn up to six shillings a day (30p), the normal pay of an average soldier was usually one shilling and nine pence (9p). In present day terms it does not seem to be much, but in 1914 it was a major inducement for some Irishmen to enlist. Army pay and allowances provided Irish working class families with a regular income for the first time. In Ireland this income was even more attractive in a society where the standards of living and rates of pay were lower than those in Britain.

In conclusion the main cause of Irish Catholics joining the British forces in 1914 was the living conditions, which they had to endure at that time. There was no thought of betraying Ireland by donning the uniform of an “occupying power”. They were concerned mainly with the survival of their children, the promise of a better life, freedom from the indignity of poverty, and the fulfilment of the British promise of “Home Rule” for all of Ireland.

![]()

![]() If you want to comment on this article and send Jim Wood an e-mail, please click .

If you want to comment on this article and send Jim Wood an e-mail, please click .

![]() Back to the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War.

Back to the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War.

![]()