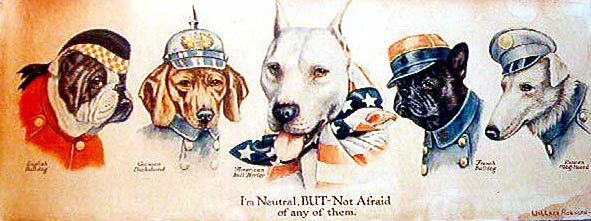

![]() American poster showing no fear in being neutral, 1915

American poster showing no fear in being neutral, 1915

The text below, by the English author Edward Wright, was published in the British weekly The War Illustrated, on 24th April 1915.

All good, earnest, "unhyphenated" Americans must have smiled when they read the reported appeal made to them by Pope Benedict. According to a German-American journalist, who obtained an interview with the Sovereign Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, the Pope went so far as to suggest that the Americans should stop the war by refusing to supply munitions. But the appeal was made too late. The Americans fully resolved last December that the war should be fought to a finish. To this end they were most eager to prevent Great Britain and France from using their superior naval power to the disadvantage of Germany.

Our country once hoped that the British and French Navies might be justifiably employed in saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of the allied troops, and bringing the war quickly to an end. But the American, anxious to show his neutrality by standing well with both contending parties, objected to any interference with his right to supply munitions to both camps. Being strictly neutral, he was ready to sell guns and shells to the Allies, but at the same time he desired to maintain a traffic in munitions with Germany. He wanted to be even-handed— using both hands to fill his pockets.

For several months past no gun, rifle, or howitzer in the German or Austrian lines could have been fired without the friendly help of the United States. The Germans needed a thousand tons of cotton every day to make their smokeless powder. Their preliminary provision of cotton bales was exhausted in the first month's of the war. It would have crippled them if they had had to put up new machinery for transforming all the cotton fabrics in Germany and Austria into the base for their nitrated powder. Moreover, their available supply of cotton fabrics would not have sufficed to maintain the war for many months. The collection of a thousand tons of cotton fabric a day would soon have denuded the Teutonic peoples to the extreme point of decency and health. The apostles of Kultur therefore had to get hundreds of thousands of tons of fresh cotton bales in order to continue their work of blowing up Rheims, Arras, and Ypres, turning Northern France and Poland into unhoused wildernesses, and killing and wounding the allied troops by the hundred thousands. The good American of unhyphenated origin, the American of the southern cotton plantations, kindly saw that the Teuton got what he wanted.

When we began at last to think of attempting to use our naval power more vigorously, we received a sharp Note in regard to the way in which we were searching ships carrying American cargoes. The complaint against us was nominally made in regard to our search for American goods which had been declared contraband of war; but the real intention was to daunt us from any attempt to interfere with the cotton trade with Germany. The American shipping Note was indeed so sharp that it almost seemed, at first, as if it would lead to the United States following the example of Turkey, and taking up arms for the support of the promoters of the new civilisations in Belgium and Poland. But we did wrong to the American in thinking that he was following the Crescent. He was only vigorously maintaining his new rights as a neutralist, andd fending off any interference with the supply of mode gunpowder to Germany and Austria-Hungary. When he had accomplished the end he had in view, his sudden warlike feelings were appeased.

IT must be admitted that the true American is really even-handed. He has no desire to see the Allies overcome for want of material which he is able to supply. After he had supplied the Germans with a new store of two hundred thousand tons of cotton, sufficient to make powder to last them another half-year, the German American League began to agitate for the stoppage of the export of war material. The Fatherland of the hyphenated Yankees had then obtained all the munition it needed for six months. This was the reason for the creation of the Neutrality League at Washington at the beginning of the present year.

But the real American resolutely continued to hold the balance between the contending armies. Russia, France, and Britain wanted 200,000,000 pounds worth of armaments and war stores, and, as the most perfect of neutralists, the American went on running his factories for the Allies. It is said he sometimes charged the Russians fifteen dollars for shells that could profitably have been sold for six dollars. But no man, or country, is without certain human weaknesses.

In any case, the American has served both sides well. Any slight irritation we might be inclined to feel in regard to his extreme sensitiveness about his cargoes with open or secret German destinations is lost in an intense admiration for his absolute even-handedness. And then he has been so kind to the Belgians. Belgium is like the poor-box by the chapel door. It helps the perfect neutralist to keep his conscience up to the Sunday morning standard, after, its sagging in the workaday toil of the week.

Edward Wright

(This text was published in the British weekly The War Illustrated, on 24th April 1915. Note the date: this was one week before the Lusitania sailed on her last voyage. When a German U-boat torpedoed this big ship and 1,195 persons on board drowned (including 124 Americans) everything changed. Suddenly America did not want to be neutral anymore.)

![]() Click here to read Barbara Tuchman's essay on how America entered the Great War.

Click here to read Barbara Tuchman's essay on how America entered the Great War.

![]() Click here to read Winston Churchill's thoughts on why America should have stayed out.

Click here to read Winston Churchill's thoughts on why America should have stayed out.

![]() Click here for a picture slide show of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe in the Great War.

Click here for a picture slide show of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe in the Great War.

![]() To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War

To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War