On April 2, 1917, the United States as a new contender entered the tournament of world power from which we have not since, despite wishful attempts, been able to withdraw. Up to then, notwithstanding our hearty belligerence in the Spanish-American War, we were not regarded as one of the Great Powers, either by them or, on the whole, by ourselves. American participation in the Great War was the beginning of our majority in world affairs.

In the half-century that has since elapsed, a fundamental shift of the international balance has taken place, with the sites of power spreading outward from Europe to the periphery. The governing seat vacated by the collapse of Britain has been taken — not without kicking and protesting against our fate; — by this country. Risen from newcomer to one of the world's two dominant powers in fifty years, we are once again at war, no longer fresh and untrained but an old hand, skilled, practiced, massively equipped, sophisticated in method, yet infirm of purpose, and without a goal that anyone can define. Is this the destiny to which that first experience has led us? How did the United States become involved and had she a choice? "God helping her," said President Wilson on that April 2 fifty years ago, "she can do no other." Could we have done other?

The Great War has never been for us so embedded a part of our national tradition as the Civil War or World War II. It is somehow less "ours." The average person thinks of it in terms of air aces who flew in open cockpits, a place called Chateau-Thierry, a song called "Over There," a form of transport called "40 and 8," and a soldier in leggings who became President Truman — but what it means in our history he could not easily say. When this writer in 1955 proposed to a prospective publisher a book on the Zimmermann telegram, a major factor in precipitating America's involvement, the advice received was to abandon the idea because it was the "wrong war"; the public was interested only in the Civil and the Second. This was in fact a justifiable assessment, much the same as that reached by a historian in 1930 who, a decade after the end of the war, found the American people still "irritated and bewildered" by it.

These words, which describe so aptly our attitude toward the war in Vietnam, establish a link between the two experiences. The first experience was governed by an old illusion, and the present experience by a new one. World War II, on the other hand, with the imperative of Pearl Harbor supplying an understood cause and purpose, did not sow doubt and self-mistrust. It was clear why we had got in and what was the end in view. But as will certainly be the case with Vietnam, so for twenty years after World War I historical controversy raged over how and why we got into it, and the question is still being probed and re-examined.

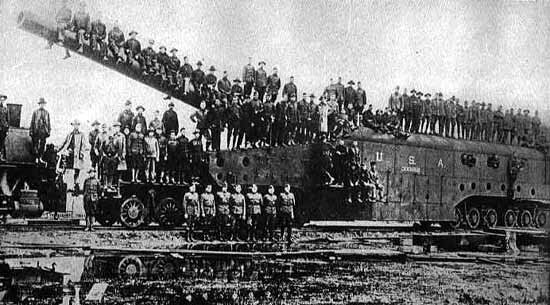

![]() German submarine harassing neutral ship

German submarine harassing neutral ship

The revisionists of the 1920s and '30s, fueled by post-war disillusion, discarded the accepted view of our involvement as the unavoidable consequence of German aggression toward neutral shipping, in favor of conspiracy theories of one kind or another. They discovered the causative factor in British propaganda, capitalist profit, and other concealed and sinister forces. Burrowing into statistics of trade and finance, private correspondence, and all manner of inner workings, the revisionists brought to light much significant material and fresh insights. But their self-accusatory thesis required a compensatory leaning-over-backward in favor of Germany, and just as they were most vigorously making their case, Germany, returning to the offensive under Hitler, unmade it for them. Since then, as is the circular fashion of history, counter-revision is leading the way back to what was obvious at the start. The somersaults of revisionists — whether it be that Roosevelt plotted Pearl Harbor or that the Third Reich, as held by England's antic historian A. J. P. Taylor, was pushed into aggression by the democracies — enjoy the notoriety of the sensational, but the facts roll over them in the end.

On the outbreak of war in 1914 the prevailing American attitude was one of self-congratulation that it was none of our affair; and there was a fixed intention that it should not become so. In classic summary — appropriately from a small town in the heart of the Midwest — the Plain Dealer of Wabash, Indiana, stated: "We never appreciated so keenly as now the foresight of our fathers in emigrating from Europe." Newspaper cartoons habitually depicted Uncle Sam separated by a large body of water from a far-off, furiously squabbling group of little figures; in one case reminding himself that the chance of his life was to "sit tight, keep his hands in his pockets and his mouth shut"; in another case standing shoulder to shoulder with President Wilson with backs firmly turned on Europe's gore-dripping "barbarians."

The belief in our safe isolation was reinforced by Wilson, who, bent on pursuing the New Freedom through domestic reform, was irritated by the threatened interference with his program from overseas. He declared in December 1914 that the country should not let itself be "thrown off balance" by a war "with which we have nothing to do, whose causes cannot touch us." (The familiar ring can be traced to a more famous echo twenty-five years later in Neville Chamberlain's reference to Czechoslovakia as "a far-away country of which we know nothing.")

![]() Wilson throwing the first pitch (at baseball, that is)

Wilson throwing the first pitch (at baseball, that is)

For Wilson it was justifiable in August 1914 to ask the American people to be "impartial in thought as well as in action... neutral in fact as well as name." But by December, when the expectation of a short war had vanished at the Marne and the armies were locked in the deadly stalemate of the trenches, the war was already touching us. Forced to recognize that American business could not be held immobile, Wilson had already in October reversed his earlier ban on loans to belligerents. This was the foundation for the economic tie which thereafter in ever-increasing strength and volume attached the United States to the Allies. By permitting extension of commercial credit it enabled the Allies to buy supplies in America from which the Central Powers, by virtue of Allied control of the seas, were largely cut off1). It opened an explosive expansion in American manufacture, trade, and foreign investments and bent the national economy to the same side in the war as prevailing popular sentiment.

For the country on the whole was as pro-Allied in sympathy as it was anti-belligerent in wish. The President shared the sentiment. "I found him," wrote Colonel House after the first month of war, "as unsympathetic with the German attitude as is the balance of the country." Counselor Von Haniel of the German Embassy in Washington, trying to disabuse his principals of certain illusions, reminded them that American feeling was the outgrowth of a natural connection with England "in history, blood, speech, society, finance, culture," and that "in the present case commercial instinct and sentiment point in the same direction." He had hit upon the essence of the situation.

At the same rime as he lifted the ban on loans, Wilson agreed to permit unrestricted trade in munitions, contrary to an earlier proposal for their embargo. The two measures were not taken in the Allied interest (although they were to work to the Allies' advantage) but in the American interest — for the Administration, no less than Von Haniel, knew the strength of the country's "commercial instinct" and feared that an embargo would turn Allied orders to Canada, Australia, and Argentina. To ban loans and embargo munitions would have been to give realistic expression to the isolation that the people and their President believed they enjoyed. But it would have closed off the wealth of unlimited orders, and Americans did not wish to surfer for their neutrality. Rather they hoped to make a good thing of it. With these two economic measures taken before the war was three months old, the fact, if not the illusion, of isolation was dead.

In February 1915 Germany declared a submarine blockade of Britain, to be carried out by a policy of "unrestricted" undersea warfare, which meant attack without warning on merchant ships found in the war zone. As a violation of traditional neutral rights to freedom of the seas, this was, said Wilson, outraged, "an extraordinary threat to destroy commerce." An American President was obliged to resist it even though a quarrel would heighten the risk of involvement. Quarrels with the British were continuous over their incursions on freedom of the seas in the form of the Declaration of London, the doctrine of continuous voyage, elaboration of contraband, the right of search, Prize Court procedures, and other annoyances which together added up to that old conflict between the belligerent's right to blockade and the neutral's right to trade. But Britain's measures, however infuriating to legalists of the State Department, did not threaten life or touch the public mind or seriously hamper the flow of goods, of which by far the major share was directed to the Allies in any case.

By contrast, acquiescence in the role claimed for the U-boat would have meant the end of overseas trade. The explicit threat to neutral civilian lives meant either that Americans must stay off the public highway of the ocean or the American government must exert enough pressure, without tipping the precarious balance of neutrality into open rupture, to make the Germans draw back. Either way, with this development, the war had not only touched but entangled us.

![]() The burning of Louvain in Belgium aroused America

The burning of Louvain in Belgium aroused America

During the next two years German activities on the seas, in Belgium, and in the plots of spies and saboteurs in the United States operated relentlessly to weaken American neutrality, with results that would have been the same with or without Allied propaganda.

Germany's violation of Belgium's guaranteed neutrality, the opening act of the war, had aroused American indignation and put Germany in the wrong from the start. It established the image of bully in the public mind. This was no sudden reversal, for the image of the kindly German professor personified by Dr. Bhaer, who married Jo in Little Women, had long since given way, under the influence of Wilhelmine Germany, to the arrogant Prussian officer. Initial American indignation would doubtless have subsided into indifference if, before the first month was out, it had not been re-excited and confirmed by the burning of Louvain and its ancient library. The horror engendered by this act was profound, for the time, it must be remembered, was on the far side of the gulf of 1914-18, when people permitted themselves simple and sentimental reactions and society was believed to be advancing in moral progress.

With the American Minister to Belgium, Brand Whitlock, former reform mayor of Toledo, remaining in Brussels in constant contact between the occupying power and the population, Americans felt a particular concern for Belgium's misfortunes, from the shooting of hostages to the developing starvation that evoked the Hoover Relief Commission. The Bryce Report on atrocities issued by England and signed, not by accident, by the Englishman best known to the United States, the former Ambassador to Washington and author of The American Commonwealth, fell on prepared ground. It gave rise to many exaggerated atrocity stories, but it was not British propaganda that staged the trial and execution of Edith Cavell. This shooting of a woman, a nurse, a humanitarian, accomplished with the unfailing German affinity for the act that would most successfully outrage world opinion, sealed the concept of the Hun.

Above all, the mass deportations, begun in 1916, of ultimately three hundred thousand Belgians to forced labor inside Germany aroused more anger than anything since the Lusitania. Whether or not because of sensitivity on the subject of slavery, Americans — at least of that day — found something peculiarly shocking about citizens of a white Western nation being carried off to forced labor. The revulsion, reported Von Haniel, "is general, deep-rooted and genuine."

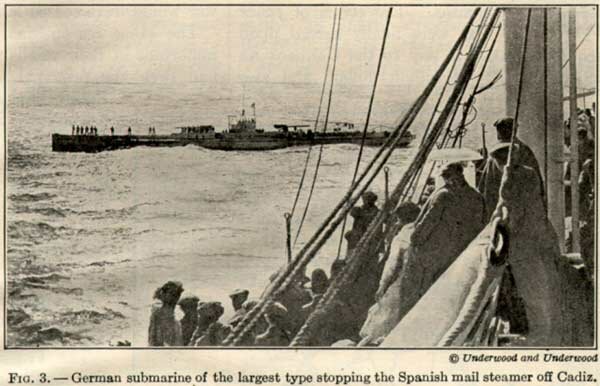

![]() Lusitania heading westward near the Old Head of Kinsale,

Lusitania heading westward near the Old Head of Kinsale,

where she would be sunk by a German submarine

The sinking in May 1915 of the Cunard Line's Lusitania, which carried, in addition to a full complement of non-combatant passengers, a part-cargo of small-arms ammunition, besides enhancing German "frightfulness," had brought to a head the issue of submarine warfare. Regarded by the Germans as a munitions carrier using its non-combatant status as protection, the ship was sunk without warning; that is, without ordering passengers off in lifeboats before loosing the torpedo. Of the nearly 2,000 persons aboard, 1,195 were lost including 124 Americans. In the previous week two American ships had been attacked with two American deaths. Thus the rights of both neutrals and non-combatants were at stake.

Tense and protracted negotiations followed in which Wilson's almost impossible task was to force Germany to acknowledge these rights without the ultimate threat of war, which was the last thing he wanted. He had to pick his way along a narrow ridge between the precipice of war on one side and that of abdication of neutral rights, as advocated by his Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, on the other. Representing the pacifist position that no interest was worth defending at the risk of war, Bryan became spokesman of the demand that Americans be warned not to (or, as some insisted, forbidden to) travel on belligerent ships.

In this demand was crystalized a central issue that transcended the matter of American trade or neutral rights. The real issue was our position as a great power. The United States could not allow the U-boats to keep her nationals off the sea lanes without forfeiting the respect of other nations, the confidence of her own citizens, and her prestige before the world. She could not forbid her own people to exercise their rights, Wilson wrote to Senator Stone, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee and a leading isolationist, "without conceding her own impotence as a nation." This was the crux, the more so as to concede impotence now would undercut the ambition which the President already had in mind: to mediate the war and save the world from its own wickedness.

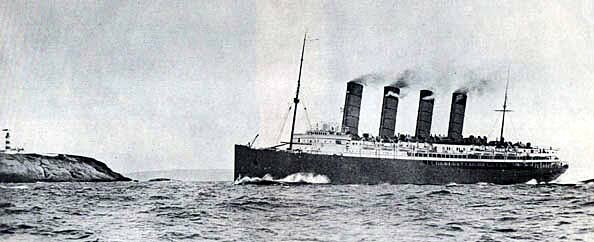

![]() William Jennings Bryan hero of the pacifist wing

William Jennings Bryan hero of the pacifist wing

Wilson rejected the proposal to keep American citizens off belligerent ships as a gesture "both weak and futile" which, by revealing the United States posture to be one of "uneasiness and hedging," would "weaken our whole position fatally." Bryan, finding his insistent and reiterated advice as Secretary of State overridden, accordingly resigned to become thereafter a trumpeting voice of the pacifist wing. While his going relieved Washington's diplomatic dinners from the temperance of grape juice, imposed by the Secretary's edict, it hardly eased matters for Wilson, who had still to make good his stand against the submarine without going to war. The pressure of the dilemma brought forth those memorable words: "There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right... There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight."

Although the speech aroused tirades of disgust by the interventionists at Wilson's "poltroonery," it reasserted the strength of the "sit-tight" sentiment in the nation which the Lusitania had so nearly dissipated.

Wilson, in note after note to Berlin, fencing, countering, reiterating, rejecting, ultimately won his point. After another ship crisis over the sinking of the Arabic in August 1915, with the loss of forty-four lives, including two Americans, he extracted a German promise not to sink without warning. But the whole issue was revived again by the sinking of the Ancona in November and the Sussex in March 1916, and was only resolved by Germany's renewal of her promise upon the President's notice that without it the United States would have no recourse but to sever relations. In fact, this result was due less to Wilson's firmness than to Germany's recognition that she had too few submarines to sink enough shipping to make the risk of American belligerency worthwhile. Her shipyards meanwhile worked round the clock to correct that inadequacy.

Each time during these months when the torpedo streaked its fatal track, the isolationist cry to keep Americans out of the war zones redoubled. When a resolution to that effect was introduced in Congress by Senator Gore of Oklahoma and Representative McLemore of Texas in February 1916, Champ Clark of Missouri, Speaker of the House, led a delegation to the White House to inform Wilson that it would pass two to one. After absorbing four and a half million words of debate, it was, however, ultimately tabled, although not without 175 votes in its favor.

As the war lengthened and hates and sufferings increased, with repercussions across the Atlantic, American public opinion lost its early comfortable cohesion. The hawks and doves of 1916, equivalent to the interventionists and isolationists of the 1930s, were the preparedness advocates and the pacifists, with the great mass of people in between still stolidly, though not fanatically, opposed to involvement.

The equivalency to the present, however, is inexact because of the sharp ideological reversal in our history that took place after 1945. The attitude of the American people toward foreign conflict in the twentieth century has been divided between those who regard the enemy or potential enemy as a threat to American interests and way of life and are therefore interventionists, and those who recognize no such danger and therefore wish us to stay at home and mind our own business. Who belongs to which group is decided by the nature of the enemy. When, as in the years before 1945, the enemy was on the right, our interventionists by and large came from the left. When, as in the years since 1945 the Soviet Union and Communist China replaced the right-wing powers of Germany and Japan as our opponents, American factions switched roles in response. The right has become interventionist and the left isolationist.

Former advocates of America First, who used to shriek against engagement outside our frontiers, are now hawks calling for more and bigger intervention (otherwise escalation). Former interventionists who once could not wait to fight the Fascists now find themselves doves in the unaccustomed role of isolationists. It is this regrouping which has made most people over twenty-five so uncomfortable.

In 1916 ideologies of right and left were less determining. The most vigorously anti-German interventionists came from the upper and educated classes especially on the East Coast, where Prussian militarism (the term then in use) was regarded as the ultimate foe of democracy which could not be allowed to triumph. President Emeritus Eliot of Harvard, "the topmost oak of New England," declared the defeat of the Central Powers to be "the only tolerable result of this outrageous war." Chief Justice White of the Supreme Court said, "If I were thirty years younger, I would go to Canada to enlist."

Distinguished clergymen like Henry Van Dyke and Lyman Abbott felt no less warmly, and the president of the American Historical Association, William Roscoe Thayer, announced in response to Wilson's original advice to be impartial in thought, that only a "moral eunuch" could be neutral in the sense implied by the "malefic dictum" of the President.

The new Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, was convinced that a German victory "would mean the overthrow of democracy in the world" by, the forces of military despotism, an opinion shared by his Republican predecessor, Elihu Root, not to mention by the President's closest adviser, Colonel House, and his bitterest despiser, ex-President Theodore Roosevelt.

The opinions of the articulate East, however, were more influential than representative. The rest of the country, with its center of gravity a thousand miles from any ocean, still bore the stamp "Keep out of it." Isolationism naturally centered in, although was not confined to, the largely Republican Midwest, with its "hyphenated" settlements of German-Americans in Milwaukee, Chicago, St. Louis, and other cities, its Populist traditions, and its agrarian radicals called sons-of-the-wild-jackass. The home states of congressional isolationist leaders tell the tale: Speaker Champ Clark and Senator Stone of Missouri, Senators Hitchcock and Norris of Nebraska, La Follette of Wisconsin, Gore of Oklahoma, and, from the South, Vardaman of Mississippi and Representative Claude Kitchin, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, from North Carolina.

Ideological divisions cut across the geographical. Progressives and Socialists, though hating the autocracies, were largely (though by no means all) isolationist, partly because they did not want war to interfere with domestic reform and partly from inherited dislike of Europe. They shunned foreign entanglements with the Old World from whose quarrels and standing armies and reactionary regimes their fathers had escaped to the promise of America. Regardless of background or position, they all joined in one dominant argument: Sentiment for war was manufactured for profit by bankers and businessmen. David Starr Jordan, pacifist president of Stanford, pictured Uncle Sam "throwing his money with Morgan & Co. into the bottomless pit of war," La Follette denounced profiteers as the real promoters of preparedness, and Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist party, declared he would rather be shot as a traitor than "go to war for Wall Street."

Foreseeing that we might, and believing that we should, enter the war, pro-Allied groups opened a preparedness campaign in 1915. Supported by the Army and Navy Leagues, they formed committees for national security and American rights, organized parades, distributed books, films, and leaflets identifying preparedness with patriotism, introduced a bill in Congress to expand the Reserve into a continental army of 400,000, and called for a congressional appropriation of $500 million to build an "adequate Navy." As the agitation mounted, vociferously led by Theodore Roosevelt, the administration forces took alarm lest in resisting it, in a diehard grip on neutrality, they allow a partisan issue ro develop in which the Republicans would become the party of patriotism and the Democrats be identified with "weakness."

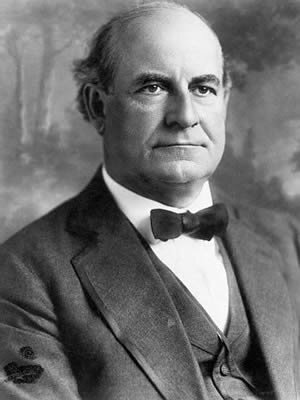

![]() Building of warships in New York

Building of warships in New York

Wilson accordingly embraced preparedness, marched straw-hatted in parades, supported the Army Bill for increasing the Regulars from 80,000 to 140,000 and the Reserves to 400,000, and approved a five-year program of naval construction to provide 10 battleships, 16 cruisers, 50 destroyers, and 100 submarines. He undertook a speaking tour through the Midwest on behalf of the Army Bill, but failed to persuade the hard core of isolationists of the need for adequate armed forces. This outcome was not surprising since he balanced every eloquent plea to prepare "not for war but for adequate national defense" with an equally eloquent avowal of his and the country's "deep-seated passion for peace."

In the spring of 1916 debate raged in Congress and country over the Army Bill. Progressives thundered against militarism as the spawn of capitalist greed and the destroyer of the American dream. Interventionists insisted America must join in the battle of the democracies against tyranny (a cause embarrassed by the inconvenient alliance of the Czar) if political freedom was to survive anywhere. Preparedness parades grew louder and longer, a mammoth example on Fifth Avenue lasting twelve hours with 125,000 civilian men and women marchers, two hundred brass bands and fifty drum corps, thousands of cheering observers on the sidewalks, and floodlights on the last squadrons as they marched on into the night. Impervious, a majority of Republican Representatives in the House voted to warn American citizens off armed merchant ships, indicating their firm preference for discretion over neutral rights.

A stunning and unexpected testimony to the depth of pacifist feeling emerged at the Democratic convention at St. Louis in June. Wilson's managers had planned to make patriotism the theme, with bands concentrating on the national anthem instead of "Dixie" and bursts of "spontaneous" enthusiasm for the flag. These demonstrations proved uninspired, but the keynote speech of ex-Governor Martin Glynn of New York, which argued that the American tradition was to stay out of war whatever the provocation, produced a frenzied outburst and a "delirium of delight."

Designed to appeal to the peace sentiment, it had been approved in advance by the President, who, no less than any other practicing politician in search of re-election, was interested in consensus. As Glynn cited each historical precedent, his audience took up the chant, "What did we do? What did we do?" and the speaker roared in reply, "We did not go to war!" Delegates cheered, waved flags, jumped on their seats. When Glynn, becoming somewhat dismayed at what he had aroused, tried to slide over his prepared text, they yelled, "No! No! Go on! Give us more! More! More!" They danced about the aisles, "half mad with joy... shouting like schoolboys and screaming like steam sirens."

Glynn had shown that pacifism, instead of being something not quite manly, was right, patriotic, and American. The effect was "simply electrifying." Convention leaders were appalled. Chairman McCombs hastily scribbled on a sheet of paper, "But we are willing to fight if necessary," signed his name, and passed it to Glynn, who nodded and called back, "I'll take care of that." But by now fascinated with his own effect on the crowd, he never did. Political plans were deranged. Wilson's campaign was revised to make peace the main issue; the Republicans, repudiating Roosevelt, nominated Hughes on a platform of "straight and honest neutrality" and lost in November to the slogan promoted by Wilson's managers, "He kept us out of war."

It was this use of the peace sentiment which accomplished the close victory through a notably sectional vote of the Western states in new alliance with the South. It enabled Wilson to recover for the Democratic party what Bryan had three times failed to win, the support of the majority of predominantly agricultural states.

The final four months leading up to U.S. belligerency began with Wilson's concerted effort through December and January to end the war through mediation. His concept of a "peace without victory," although called by Senator La Follette "the greatest message of the century," did not appeal to the belligerents. Since neither side wanted the American President to arrange the terms of a settlement and each was bent on total victory, Wilson's attempt to negotiate a peace failed.

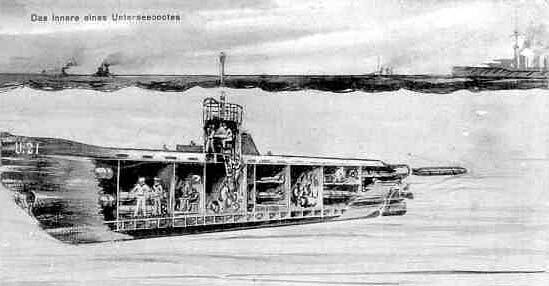

![]() The interior of a submarine, German postcard

The interior of a submarine, German postcard

In the meantime Germany, having built up a fleet of two hundred submarines, took the decision to risk American hostility for the sake of an all-out effort to end the war her way. On January 31, 1917, she formally notified Washington of intent to resume unrestricted submarine warfare beginning next day. All neutral ships would be "forcibly prevented" from reaching England. A single exception in the form of one U.S. passenger ship a week would be allowed provided that it carry no contraband, dock only at Falmouth and only on a Sunday, be marked by three vertical stripes each a meter wide painted alternately white and red, and fly at each mast a large flag checkered white and red.

At the prospect of funnels "striped like a barber's pole and a flag like a kitchen tablecloth," the American historian J. B. McMaster could hardly contain his indignation. The insult implied in such orders addressed to the major neutral indicated that Germany had no doubts of America's answer. "We are counting on the probability of war with the United States," Field Marshal von Hindenburg had said at Supreme Headquarters when the decision was taken, but "things cannot be worse than they are now. The war must be brought to an end by whatever means as soon as possible." Headquarters had convinced itself that in the time before the submarine could knock out the Allies, American military assistance would "amount to nothing." But the civilian Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg believed the entry of America meant "finis Germaniae."

In the vortex of the conflict, America had become, willing or not, a major power: as arsenal and bank of the Allies, to whose cause our economy no less than our political system was now attached, and as obstacle, so long as we continued to supply the Allies, to any German hope of victory. To yield freedom of the seas now after two years' hard-fought maintenance of the principle was incompatible with first-class status. Wilson was left with no choice but to declare the long-avoided rupture of relations. At once pacifist groups were roused to feverish action in mass meetings to demand that American ships stay out of war zones, while interventionists agitated equally loudly for the arming of our ships and the aggressive assertion of American rights.

As ships piled up in home ports, American commerce threatened to come to a standstill affecting the entire national economy. The Cabinet grew seriously alarmed. Although Wilson possessed the executive authority to arm ships, he was reluctant to take the step that would inevitably start the shooting. He preferred to ask Congress for authorization, thus touching off the great debate and filibuster on the Armed Ship Bill.

In the midst of it came the revelation of the telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann inviting Mexico into alliance as a belligerent. As a scheme to keep U.S. forces occupied on their own border, it offered to help Mexico regain her lost territories of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Intercepted and decoded by British naval intelligence and made available to this country, the telegram was released to the press on March 1 in the hope of influencing "the little band of willful men" in the Senate. It failed of that purpose, but aroused the American public more than anything since the outbreak of war. As a proposed assault on U.S. territory, it convinced Americans of German hostility to this country.

On March 9 Congress adjourned without passing the bill. The President issued the order for arming ships anyway and waited for the "overt act". It came on March 18 in the torpedoing without warning of three American merchant ships with heavy loss of life. Conveniently at this moment the overthrow of the Czar by the preliminary revolution in Russia purified the Allied cause, and the advent of the great new convert to democracy under the Kerensky regime brought a glow of enthusiasm to liberal hearts. At the same time the relentlessly mounting toll of the submarine was making a graveyard of the Atlantic and raising a serious prospect of the Allies' defeat.

For two more weeks the President hesitated in his agony, afflicted by his sense, as he had said earlier that month, that "matters outside our life as a nation and over which we had no control... despite our wish to keep free of them" were drawing the country into a war it did not want". If any nation now neutral should be drawn in", he had said in November, "it would know only that it was drawn in by some force it could not resist".

This is as just a statement of the truth as any. We were not artificially maneuvered to a fate that might have been otherwise; what engulfed us were the realities of world conflict. In the latest of a long tram of scholars' examinations, Ernest May of Harvard in his 'The World War and American Isolation, 1914-17', published in 1959, concluded, "Close analysis cannot find the point at which he [Wilson] might have turned back and taken another road".

On April 2 Wilson went to Congress to ask for its formal acceptance of "the status of belligerent that has been thrust upon it." He put the blame specifically on submarine warfare: "a war against all nations". He said "neutrality is no longer feasible or desirable" when the peace of the world and freedom of its people are menaced "by the existence of autocratic governments backed by force which is controlled wholly by their will, not by the will of the people".

The validity of this proposition was somewhat weakened by the fact that he had believed neutrality feasible and eminently desirable in coexistence with these same nations for nearly three years. "A steadfast peace", he now discovered, "can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations". Citing the Zimmermann telegram as evidence of hostile purpose, he said there could be no assured security for the democracies in the presence of Prussian autocracy, "this natural foe of liberty". And so to the final peroration: "The world must be made safe for democracy... the right is more precious than peace".

Nothing that Wilson said about the danger to democracy could not have been said all along. For that cause we could have gone to war six months or a year or two years earlier, with incalculable effect on history. Except for the proof of hostility in the resumed submarine campaign and the Zimmermann telegram, our cause would have been as valid, but we would then have been fighting a preventive war - to prevent a victory by German militarism with its potential danger to our way of life; - not a war of no choice. Instead, we waited for the overt acts of hostility which brought the war to us.

The experience was repeated in World War II. Prior to Pearl Harbor the threat of Nazism to democracy and the evidence of Japanese hostility to us was sufficiently plain, on a policy level, to make a case for preventive war. But it was not that plain to the American people, and we did not fight until we were attacked.

In our wars since then the assumption of responsibility for the direction, even the policing, of world affairs has been almost too eager — as eager as it was formerly reluctant. In what our leaders believe to be a far-sighted apprehension of future danger, and before our own shores or tangible interests have been touched, we launch ourselves on military adventure half a world away with the result that the country, as distinct from the government, does not feel itself fighting in self-defense. Korea was thoroughly unpopular and Vietnam — where we have gone a step further into a purely preventive war, to contain Chinese communism - even more so. In the circumstances the instinct of the country is uneasy, consciences troubled, and counsels divided.

Two kinds of war, acquisitive and preventive, make hard explaining and the last more so than the first. Although the first might be considered less moral, so far in human experience abstract morality has not notably determined the conduct of states and a good, justifiable reason like need, or irredentism, or "manifest destiny," can always be found for taking territory. Besides, acquisitive wars tend to be short, sharp, and successful and success never needs explaining. But it is never possible to prove a preventive war to have been necessary, for no one can ever tell what would have happened without it. Given the gap in modern power and organized resources between China and ourselves, our exaggerated fear of Chinese communism, both as threat to us and in its appeal to the rest of Asia, seems unwarranted by a "clear and present danger". In the grip of a new illusion we have not waited, as in World Wars I and II, for the enemy's shot to be aimed at us.

In April 1917 the illusion of isolation was destroyed. America came to the end of innocence, and of the exuberant freedom of bachelor independence. That the responsibilities of world power have not made us happier is no surprise. To help ourselves manage them, we have replaced the illusion of isolation with a new illusion of omnipotence. That screen, too, must fall.

Where once we saw ourselves self-contained and free to stand apart, we now see ourselves as if endowed with some mission to organize the world in our image. Militarily we could knock out Hanoi, and doubtless Peking, too, tomorrow, but we cannot raise a clean new democracy on nuclear ashes. Whatever our material or political power, it is not enough for omnipotence. We cannot mold the non-Western world to our desires nor require its acceptance of our concepts of political freedom and representative government. It is too late in history to export to the nations of Asia and Africa with unschooled and undernourished populations in the hundreds of millions the democracy that evolved in the West over a thousand years of slow, small-scale experience from the Saxon village moot to the Bill of Rights. They have not had time to learn it and history is not going to give them time. Meanwhile we live on the same globe. The better part of valor is to spend it learning to live with differences, however hostile, unless and until we can find another planet.

- - -

Barbara W. Tuchman was born in 1912 in New York City. After graduating from Radcliffe she took a job with the Institute for Pacific Relations in 1933. In 1935 her father, Maurice Wertheim, purchased The Nation, and she started writing for that magazine. In 1937 she went to Madrid to cover the Spanish Civil War for The Nation and wrote passionately in support of the loyalist government. She deplored the United States' failure to participate in the war, and thereafter the theme of how good is crushed or subverted ran throughout her work. In 1943 she became an editor at the U.S. Office of War Information. In 1960 her book The Guns of August, a narrative history of the outbreak of World War I, won the Pulitzer Prize. Another book she wrote on the Great War was The Zimmermann Telegram. She also wrote some essays on the subject of the First Worldwar, such as the one above and Woodrow Wilson on Freud's Couch, which appeared in 1967 in The Atlantic. She won the Pulitzer Prize again in 1971 for her book Stilwell and the American Experience in China: 1911-45. In her later years Tuchman was a lecturer at Harvard University and at the U.S. Naval War College. Her book The First Salute, about the American Revolution, was on the New York Times best-seller list when she died in 1989.

Barbara W. Tuchman was born in 1912 in New York City. After graduating from Radcliffe she took a job with the Institute for Pacific Relations in 1933. In 1935 her father, Maurice Wertheim, purchased The Nation, and she started writing for that magazine. In 1937 she went to Madrid to cover the Spanish Civil War for The Nation and wrote passionately in support of the loyalist government. She deplored the United States' failure to participate in the war, and thereafter the theme of how good is crushed or subverted ran throughout her work. In 1943 she became an editor at the U.S. Office of War Information. In 1960 her book The Guns of August, a narrative history of the outbreak of World War I, won the Pulitzer Prize. Another book she wrote on the Great War was The Zimmermann Telegram. She also wrote some essays on the subject of the First Worldwar, such as the one above and Woodrow Wilson on Freud's Couch, which appeared in 1967 in The Atlantic. She won the Pulitzer Prize again in 1971 for her book Stilwell and the American Experience in China: 1911-45. In her later years Tuchman was a lecturer at Harvard University and at the U.S. Naval War College. Her book The First Salute, about the American Revolution, was on the New York Times best-seller list when she died in 1989.

1)- England and France were not very happy about the way America conducted 'neutralism' in the time before the United States declared war on Germany. Click here to read what the English author Edward Wright wrote in 1915 about this subject.

![]() To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War

To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War

![]() Click here if you want to read more about the origins and causes of the Great War.

Click here if you want to read more about the origins and causes of the Great War.

![]() Click here for a challenging opinion why America should have stayed out of World War I.

Click here for a challenging opinion why America should have stayed out of World War I.

![]() Click here for another dissent voice on the result of America's entry in the Great War.

Click here for another dissent voice on the result of America's entry in the Great War.

![]() Click here for pictures of the American Expeditionary Force in the Great War.

Click here for pictures of the American Expeditionary Force in the Great War.