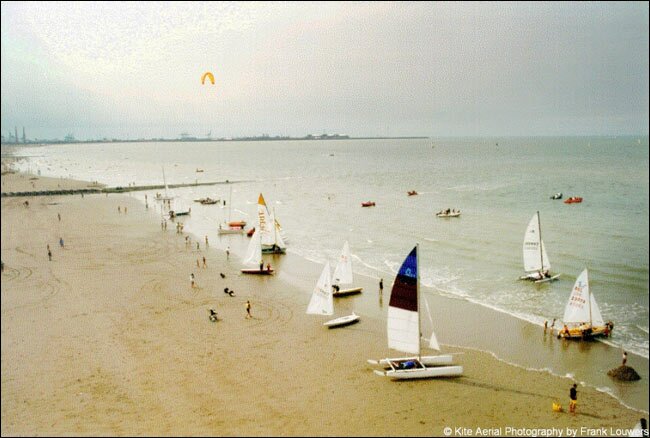

![]() The beach at Knokke. In the distance the port of Zeebrugge

The beach at Knokke. In the distance the port of Zeebrugge

Picture courtesy , Belgium

Surfers ride the waves, the sun caresses the beach-goers and children play in the sand. Knokke, Duinbergen and Heist — beautiful Flemish holiday resorts. But, according to some, warning signs should be posted on these beaches that read:

WARNING! MUSTARD-GAS DANGER!

Maybe these signs also belong rightly on Holland's Zeeland beaches. But most people in Zeeland are unaware, and the governments of Belgium and Holland are literally sticking their heads in the sand. Belgium's scandal lies right at the coast and it doesn't respect national borders.

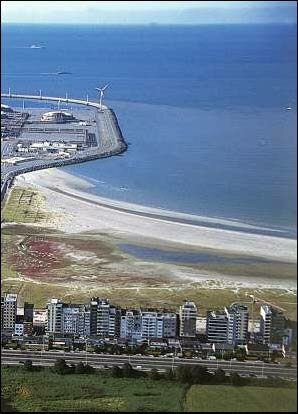

"Confidential" and "Limited dissemination" is written on almost all official Belgian documents that refer to an unknown amount of poison gas lying in the sea right off Knokke and very near the busy port of Zeebrugge (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT). Only a few hundred meters from the beach. At two meters depth.

"Confidential" and "Limited dissemination" is written on almost all official Belgian documents that refer to an unknown amount of poison gas lying in the sea right off Knokke and very near the busy port of Zeebrugge (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT). Only a few hundred meters from the beach. At two meters depth.

Confidential—so the authorities can turn their head away. Limited dissemination—so most people in Belgium and in the Netherlands have never heard about it.

Belgian officials become frightened, claim illness, or refuse to take calls when questions are asked.

"It is a pity that this is coming to light right before the tourist season," says the former Mayor of Knokke, Manu Desutter, who is now a member of parliament. He knows about the poison gas, but he fears the effects of publicity on the tourist industry along the coast.

"Everything is scrupulously kept quiet, sir," acknowledges the head of the tourist office in Knokke. He leads the curious, who ask what the yellow beacons in the sea are for, to believe they mark an area of quicksand.

Senator Michael Maertens from Diksmuide is one of the few who wants transparency: "To me it's a fact that millions of tons of munitions were dumped on the sea floor. A secret report by the Army that I unfortunately cannot allow you to see, makes it perfectly clear that a large amount consists of poison gas."

Mustard Gas

That Army report is not the only source of information. In one of the Bulletins of the Atomic Scientists, researcher J. P. Zanders of the Belgian Free University calculated that about 1.1 million liters of pure poison gas must lie here: above all, mustard gas.

And the toxicologist from Gent, Prof. A. Heyndricks, an international expert in the area of poison gas, says: "The Belgian Army wants us to delude us that this mustard gas is quickly broken up by sea water, but that is absolutely untrue. It remains deadly. When one of the shells breaks, the mustard gas comes free and can wash ashore on the beach in the form of small clumps."

Sen. Maertens wants swimmers, divers, surfers, and beach-goers warned of the danger. He wants clear signs on the beach. That must happen "very quickly" in his opinion. "Taking measures must not wait until children or swimmers on the beach kick a clump of mustard gas."

Maertens alludes here to the Belgian beaches, but how do things stand along the Dutch beaches? The Dutch salvage expert Roel Donker explains the effect of sea currents in this region: "The tidal flow is shorter and is stronger than the ebb, such that everything that is produced in Belgium comes right toward the northeast."

Whoever looks at the map sees the danger for himself: just a few kilometers to the northeast stretch the beaches of Dutch Zeeuws-Vlaanderen and Walcheren. That's where you find popular Dutch seaside resorts like Cadzand, Zoutelande, Westkapelle, and Domburg.

Horse Market

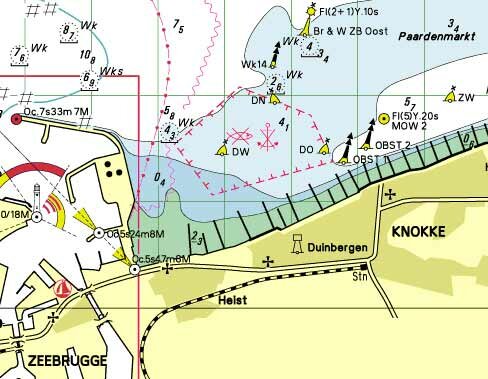

The Paardenmarkt (Horse Market): the name given to the narrow sand-bank that, right along the Belgian coast, extends from Zeebruge to the Netherlands border. The official sea map shows a depth of from 1.2 to at most 4 meters.

The Paardenmarkt (Horse Market): the name given to the narrow sand-bank that, right along the Belgian coast, extends from Zeebruge to the Netherlands border. The official sea map shows a depth of from 1.2 to at most 4 meters.

On sea map D11 (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT) five dotted lines are drawn on this sand-bank that form a pentagon, right in front of the beach at Knokke. Inside this pentagon there is a fish plus an anchor drawn with a stripe through them. That means that neither fishing nor anchoring are allowed in this area.

The area is barely two square kilometers. Beacons (that are clearly visible from the beach at Knokke) mark the corners.

There are poison gas shells and other munitions in at least seventeen spots inside this area. The stuff is partially covered by a layer of rotting slime.

The poison gas has lain there for 75 years. It dates from the time of the First World War. It was discovered in 1971 by dredging crews and kept quiet, very quiet, by the Belgians.

Battlefields

In November 1918, when the soldiers left the Western Front in Flanders and went home, awe-inspiring amounts of unused ammunition remained behind. Millions of shells of French, British and German manufacture. A great number contained poison gas.

The British were the first to dump their unused ammunition into the sea here. In the Public Records Office in Kew, near London, is a dossier about these transports. In the period from June until September 1919, the British sent at least sixteen hundred rail cars to Zeebrugge.

There, on the jetty, the munitions were transferred to unloaders (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT), who let the shells fall into the sea just to the east of the harbor mouth. The dumping-ground was curiously unmarked in the British dossier but was pretty certain: the sand-bar named Paardenmarkt (Horse Market).

There, on the jetty, the munitions were transferred to unloaders (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT), who let the shells fall into the sea just to the east of the harbor mouth. The dumping-ground was curiously unmarked in the British dossier but was pretty certain: the sand-bar named Paardenmarkt (Horse Market).

In November of that same year 1919, the Belgian army began dumping on Paardenmarkt. This time it was German munitions that had been left behind on the battlefields, often still in their factory boxes and crates.

Fear

In a newspaper account of a parliamentary debate in Belgium in 1919, the government is said to have then considered dumping into the sea as the only solution. The motivation seemed to be "because the people are especially afraid of poison gas after munitions exploded in dozens of places that led to dozens of deaths."

How much the Belgians dumped in those years, no one knows. Newspaper stories at that time speak of "daily" and the movement of a "few hundred" rail cars. In a secret Belgian Navy report from 1972 it was estimated that it was around 340 tons per day. The operation, under the leadership of artillery officer De Ridder, lasted six months.

Another government report that dates from July 17, 1990, discloses that the Belgians at the time dumped mainly German 77 mm shells. "From the German army's equipment data, it can be estimated that one-third of the munitions may be poison, of which most would be mustard gas." One shell contains three-quarters of a liter of mustard gas, according to the report.

Houthulst

Senator Maertens estimates that a hundred times as much poison gas lies here as in the Houthulst woods. Ten thousand poison gas shells lie stacked in that West Flanders forest, every one a dud that was uncovered by plowing or construction work. These shells lie in the open air in the forest, rusting through, and are barely guarded.

Maertens: "If that parcel in Houthulst should blow up, the gas would destroy and kill everything within a nine kilometer radius. From the Netherlands I wouldn't worry too much about it, since the distance to the Dutch border is about 40 kilometers. But what's here in the sea, that's another story. This is also a serious problem for the Netherlands."

Maertens recognizes that the Horse Market lies right next the harbor at Zeebrugge. He dares not even think what could happen if another ship were to run aground on the sand-bar, as has happened before (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT: German motorvessel Heinrich Behrmann stranded on the Knokke beach, November 2001).

Maertens recognizes that the Horse Market lies right next the harbor at Zeebrugge. He dares not even think what could happen if another ship were to run aground on the sand-bar, as has happened before (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT: German motorvessel Heinrich Behrmann stranded on the Knokke beach, November 2001).

Maertens also fears that something is happening now. The Paardenmarkt is biologically completely dead, while plant life thrives in the surrounding area. "If this is happening, for example, because of waste or chlorides from the harbor of Zeebrugge, or if it's being released from poison gas, no one knows. It's never been investigated."

The Universe

Opinions differ considerably about the danger that poison gas presents for people,. Manu Desutter, member of the Senate for the Christian People's Party, thinks that it can do no harm. He accuses his colleague Maertens (the Senator for the Greens) of demagogery and sowing panic.

Desutter: "I have participated for thirty years in the city politics of Knokke and I have never heard of anyone becoming sick on our beach."

Desutter finds that doing nothing is the best solution. "Now and then such a shell or bomb will rust through. Then a little air ball will rise in the water, but that is certainly a very tiny amount in comparison with the universe. I don't really worry about it."

Toxicology professor, Dr. Heyndrickx, a Belgian poison gas expert who is internationally recognized (he assisted the Japanese in Tokyo with the sarin affair), does worry. "Chlorine gas and phosphorous break apart in the water, but mustard gas absolutely not. It remains very dangerous and active."

Prof. Heyndrickx finds it "absolutely necessary" that measuring stations be built in the noted areas that can warn as soon as mustard gas breaks free. He has time and again in the past pressed the matter, "in vain," he says.

Heyndrickx is delighted over the attention that the matter has recently created in the Dutch press. "Only when the press gets involved will something happen in Belgium."

Via the skin

Mustard gas is a colorless, oily liquid that slowly evaporates. The gas is especially dangerous for the eyes and breathing passages. Whoever takes in two grams, dies. It can also penetrate via the skin. Five grams on the skin is deadly.

The Dutch salvage expert Roel Donker has delved into the problems with mustard gas. "When a shell rots through, the mustard gas flows very rusty in the water. Below 14 degrees centigrade (57 degrees Fahrenheit), it remains neutral. It creates a kind of crust around it, just like when you leave a clump of fat lying around a while..."

"But then the clump washes ashore. The sun shines, it's warm, the crust melts... I don't want to sound cynical, but an hour later that beach will be really empty. And it will be a terribly long time before the authorities come along to let it be known what was happening. For the gas vanishes; the waste as it were, dissolves slowly."

Good condition

The earlier cited Belgian Army report mentions that Navy divers brought up several gas shells from the water in 1972 at Paardenmarkt. In 1995 some more shells were salvaged. The shells (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT) were in "relatively good condition." But for how long?

The earlier cited Belgian Army report mentions that Navy divers brought up several gas shells from the water in 1972 at Paardenmarkt. In 1995 some more shells were salvaged. The shells (PICTURE ON THE RIGHT) were in "relatively good condition." But for how long?

Senator Maertens cites Danish reports that suggest that the covers of such shells could be rusted through within years, but no one knows for sure. Few feel like recovering all shells. Prof. Heyndrickx: "When you bring the shells out of the water, a number of them will inevitably explode. You're going to suffer even worse. The danger is so great that, in my opinion, it does not outweigh the risk of letting them lie. The supply of sand from the North Sea at this site is such that we nevertheless get some protection."

He says he was approached several years ago by the Dutch salvage company Smit Tak that was interested in raising the shells. But Erik ter Haar Romeny van Smit International (of which Smit Tak is part) says when asked, "It is extremely dangerous stuff. We don't even want to touch it. As far as we're concerned, let it lie."

A salvage worker, Roel Donker says, "As long as the shells lie under the stand, they don't rot so fast. So long as no oxygen gets to them. But over a few years, over ten or twenty years, at a given moment they are nevertheless at a point."

European problem

Senator Maertens says "They can't lie there forever. We must do something. And it's so expensive that Belgium can't carry the cost alone. I find it a matter of European interest."

That raises the question of what neighboring France actually did with the poison gas that remained behind in the French portion of the Western Front. France had no better solution. In the north, near Vimy, Loos, and Verdun, there are large assembly sites — similar to Houthulst — with half-rusted shells. These are also often filled with poison gas. And there too there are regular accidents.

And this isn't all. Maertens points to the sea map. Just above the harbor of Dunkirque, in French territory, there are still four of these ominous sites with dotted lines and fish and anchors with stripes through them. "But the French are even quieter than the Belgians."

The senator has an idea how the poison gas can be cleaned up in the meantime: He wants to reclaim the land from the sea, create a polder:

"In the Houthulst woods, the Belgian Army has built a factory to make poison gas shells harmless. We of course can't bring these things out of the see at Knokke and tranport them to Houthulst. That is too dangerous. But if we were to dry out Paardenmarkt and make an island of it, like you in the Netherlands have done with Neeltje Jans? Then we could build a factory on it like the one in Houthulst."

Erik ter Haar Romeny van Smit International reacts: "That seems to me a brilliant idea."

![]() Nederlandstalige versie (Dutch version).

Nederlandstalige versie (Dutch version).

![]() To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War

To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War