The subjects of his 'Natural History of the Dead'

Hemingway's Early Encounters with Death

Hemingway's Early Encounters with Death

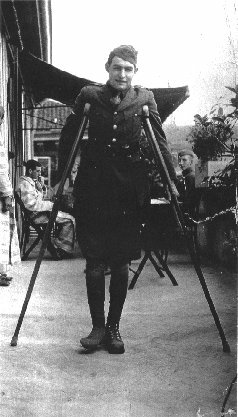

As soon as America decided to enter the Great War, Ernest Hemingway, a young reporter for the Star newspaper in Kansas City, tried to join the army. He was repeatedly rejected for military service because of a defective eye, but finally he managed to sign up for ambulance duty in Italy as a member of an American Red Cross Field Service unit (see picture left).

He was 18 years old, and on the day of his arrival in Milan a munitions factory blew up. Together with the other volunteers in his contingent Hemingway was assigned to gather up the remains of the dead.

Only three months later, in July, he was injured near Fossalta, on the Austro-Italian front at the Piave river, north of Venice.

On this river the front had stabilized after the Austrian breakthrough at Caporetto in 1917 - an event that caused an almost total collapse of the Italian army. In the period 15-24 June 1918 the Austrians again tried to push through the Piave defenses, but this came to worse than nothing (they crossed the river but were beaten back), the attackers losing 100,000 men. Hemingway endured most of this battle.

On July 8, 1918, shortly after midnight, when Hemingway was passing out coffee, cigarettes and chocolates to Italian troops in a trench, an canister from an Austrian Minenwerfer (trench mortar) exploded, lodging 227 metal fragments in his feet and legs. It was six days before his nineteenth birthday.

Not dead anymore

Later, in a letter, Hemingway wrote: "There was one of those big noises you sometimes hear at the front. I died then. I felt my soul or something coming right out of my body, like you'd pull a silk handkerchief out of a pocket by one corner. It flew all around and then came back and went in again and I wasn't dead any more."

He crumpled up and two Italian stretcher bearers started over the parapet with him, knowing that he needed swift attention. Austrian machine gunners spotted the party and the three went down under a storm of machine gun bullets, one of which got Hemingway in the shoulder and another ripped through his right knee.

According to Hemingway one Italian was killed instantly, while the other stretcher bearer had both his legs blown off. A third Italian, who had been standing a few feet away, was badly wounded and this one Ernest, after he had regained consciousness, picked up on his back and carried to the first aid dugout. He later wrote he did not remember how he got there, nor that he carried the man, until the next day, when an Italian officer told him all about it and said that it had been voted to give him a valor medal for the act.

In Love

Decorated with the Italian silver Croce di Guerra for heroism and hospitalized in Milan, Hemingway fell in love with the beautiful American Red Cross nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky, seven years his senior.

Decorated with the Italian silver Croce di Guerra for heroism and hospitalized in Milan, Hemingway fell in love with the beautiful American Red Cross nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky, seven years his senior.

Agnes actually saved his leg, as the doctors in the hospital had decided that amputation would be the quickest and most effective way to deal with his many injuries. Moved by Hemingway's concern, Agnes convinced the doctors to pursue other treatments, and they operated on him more than a dozen times. The tall grey-eyed nurse from Pennsylvania looked after him during his nine months of convalescence.

PICTURE RIGHT: Hemingway in the Milan hospital.

Agnes even promised to follow Hemingway to America and marry him. Instead, after a while she fell in love with an Italian major, a Neapolitan duke, and broke off the relationship with a 'Dear Ernest' letter, letting him know that "I am now & always will be too old & I can't get away from that fact that you're just a boy- a kid. I expect to be married soon. And I hope & pray that after you have thought things out, you'll be able to forgive me & start a wonderful career & show what a man you really are."

Six months later, in June 1919, Agnes wrote him again and told him that the Duke's mother had refused to permit his marriage to an 'American adventuress,' and hinted that she wished to renew the romance, but Hemingway did not reply. In 1921 he married Hadley Richardson from St. Louis, who was eight years older than he (Agnes attended to his wedding).

Agnes von Kurowsky eventually stood model for Catherine Barkley, the heroine of his Great War novel A Farewell to Arms.

Traumatic

Some critics have argued that Hemingway's near fatal injury on the Italian front was a traumatic event that lies at the source of most of his writing. Courageous as he had been and wounded though he was, Hemingway began embellishing the story of what had happened within a week of the incident. There is no real proof for his story that he had gotten up following the mortar blast, shouldered a wounded soldier and carried the man more than 150 yards while being fired upon.

Later he would also tell that he subsequently enlisted in the Italian army, fought with its fabled shock troops, the Arditi, and had an aluminum kneecap as a souvenir of his service with them. Journalists and biographers found no proof for these claims either.

Hemingway used many of his experiences in the Great War in his writings. Manifest is such in some of his poems and in A Farewell to Arms - but also many characters in his short stories have been directly affected by the First World War: Krebs of Soldier's Home, Harry of The Snow of Kilimanjaro, and Nick Adams of A Way You'll Never Be. The war also plays out in the stories Now I Lay Me and In Another Country.

The most gruesome scenes Hemingway witnessed he saved for his short story A Natural History of the Dead, one of the most chilling of all written contributions to this apocalypse. Hemingway wrote the bitter and cynical parody between January 1929 and August 1931. It was first published in 1933.

Because of copyright restrictions we cannot bring that complete short story here. Instead, you will find below some excerpts, beginning with a description of the situation he encountered when he, on his very first day in Italy, was sent to the munitions factory...

"Until the dead are buried they change somewhat in appearance each day"

![]() Arriving where the munition plant had been, some of us were put to patrolling about those large stocks of munitions which for some reason had not exploded, while others were put at extinguishing a fire which had gotten into the grass of an adjacent field; which task being concluded, we were ordered to search the immediate vicinity and surrounding fields for bodies. We found and carried to an improvised mortuary a good number of these and, I must admit, frankly, it was a shock to find that these dead were women rather than men. In those days women had not yet commenced to wear their hair cut short, as they did later for several years in Europe and America, and the most disturbing thing, perhaps because it was the most unaccustomed, was the presence and, even more disturbing, the occasional absence of this long hair.

Arriving where the munition plant had been, some of us were put to patrolling about those large stocks of munitions which for some reason had not exploded, while others were put at extinguishing a fire which had gotten into the grass of an adjacent field; which task being concluded, we were ordered to search the immediate vicinity and surrounding fields for bodies. We found and carried to an improvised mortuary a good number of these and, I must admit, frankly, it was a shock to find that these dead were women rather than men. In those days women had not yet commenced to wear their hair cut short, as they did later for several years in Europe and America, and the most disturbing thing, perhaps because it was the most unaccustomed, was the presence and, even more disturbing, the occasional absence of this long hair.

![]() I remember that after we had searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments. Many of these were detached from a heavy, barbed wire fence which had surrounded the position of the factory and from the still existent portions of which we picked many of these detached bits which illustrated only too well the tremendous energy of high explosive. Many fragments we found a considerable distance away in the fields, they being carried farther by their own weight.

I remember that after we had searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments. Many of these were detached from a heavy, barbed wire fence which had surrounded the position of the factory and from the still existent portions of which we picked many of these detached bits which illustrated only too well the tremendous energy of high explosive. Many fragments we found a considerable distance away in the fields, they being carried farther by their own weight.

![]() A naturalist, to obtain accuracy of observation, may confine himself in his observations to one limited period and I will take first that following the Austrian offensive of June, 1918, as one in which the dead were present in their greatest numbers, a withdrawal having been forced and an advance later made to recover the ground lost so that the positions after the battle were the same as before except for the presence of the dead.

A naturalist, to obtain accuracy of observation, may confine himself in his observations to one limited period and I will take first that following the Austrian offensive of June, 1918, as one in which the dead were present in their greatest numbers, a withdrawal having been forced and an advance later made to recover the ground lost so that the positions after the battle were the same as before except for the presence of the dead.

![]() Until the dead are buried they change somewhat in appearance each day. The color change in Caucasian races is from white to yellow, to yellow-green, to black. If left long enough in the heat the flesh comes to resemble coal-tar, especially where it has been broken or torn, and it has quite a visible tarlike iridescence. The dead grow larger each day until sometimes they become quite too big for their uniforms, filling these until they seem blown tight enough to burst. The individual members may increase in girth to an unbelievable extent and faces fill as taut and globular as balloons.

Until the dead are buried they change somewhat in appearance each day. The color change in Caucasian races is from white to yellow, to yellow-green, to black. If left long enough in the heat the flesh comes to resemble coal-tar, especially where it has been broken or torn, and it has quite a visible tarlike iridescence. The dead grow larger each day until sometimes they become quite too big for their uniforms, filling these until they seem blown tight enough to burst. The individual members may increase in girth to an unbelievable extent and faces fill as taut and globular as balloons.

![]()

The surprising thing, next to their progressive corpulence, is the amount of paper that is scattered about the dead. Their ultimate position, before there is any question of burial, depends on the location of the pockets in the uniform. In the Austrian army these pockets were in the back of the breeches and the dead, after a short time, all consequently lay on their faces, the two hip pockets pulled out and, scattered around them in the grass, all those papers their pockets had contained. The heat, the flies, the indicative positions of the bodies in the grass, and the amount of paper scattered are the impressions one retains. The smell of a battlefield in hot weather one cannot recall. You can remember that there was such a smell, but nothing ever happens to you to bring it back.

The surprising thing, next to their progressive corpulence, is the amount of paper that is scattered about the dead. Their ultimate position, before there is any question of burial, depends on the location of the pockets in the uniform. In the Austrian army these pockets were in the back of the breeches and the dead, after a short time, all consequently lay on their faces, the two hip pockets pulled out and, scattered around them in the grass, all those papers their pockets had contained. The heat, the flies, the indicative positions of the bodies in the grass, and the amount of paper scattered are the impressions one retains. The smell of a battlefield in hot weather one cannot recall. You can remember that there was such a smell, but nothing ever happens to you to bring it back.

![]() The first thing that you found about the dead was that, hit badly enough, they died like animals. Some quickly from a little wound you would not think would kill a rabbit. They died from little wounds as rabbits die sometimes from three of four small grains of shot that hardly seem to break the skin. Others would die like cats; a skull broken in and iron in the brain, they lie alive two days like cats that crawl into the coal bin with a bullet in the brain and will not die until you cut their heads off. Maybe cats do not die then, they say they have nine lives, I do no know, but most men die like animals, not men.

The first thing that you found about the dead was that, hit badly enough, they died like animals. Some quickly from a little wound you would not think would kill a rabbit. They died from little wounds as rabbits die sometimes from three of four small grains of shot that hardly seem to break the skin. Others would die like cats; a skull broken in and iron in the brain, they lie alive two days like cats that crawl into the coal bin with a bullet in the brain and will not die until you cut their heads off. Maybe cats do not die then, they say they have nine lives, I do no know, but most men die like animals, not men.

![]() The only natural death I've ever seen, outside of loss of blood, which isn't bad, was death from Spanish influenza. In this you drown in mucus, choking, and how you know the patient's dead is: at the end he turns to be a little child again, though with his manly force, and fills the sheets as full as any diaper with one vast, final, yellow cataract that flows and dribbles on after he's gone.

The only natural death I've ever seen, outside of loss of blood, which isn't bad, was death from Spanish influenza. In this you drown in mucus, choking, and how you know the patient's dead is: at the end he turns to be a little child again, though with his manly force, and fills the sheets as full as any diaper with one vast, final, yellow cataract that flows and dribbles on after he's gone.

![]()

It was not always hot weather for the dead, much of the time it was the rain that washed them clean when they lay in it and made the earth soft when they were buried in it and sometimes then kept on until the earth was mud and washed them out and you had to bury them again. Or in the winter in the mountains you had to put them in the snow and when the snow melted in the spring some one else had to bury them.

It was not always hot weather for the dead, much of the time it was the rain that washed them clean when they lay in it and made the earth soft when they were buried in it and sometimes then kept on until the earth was mud and washed them out and you had to bury them again. Or in the winter in the mountains you had to put them in the snow and when the snow melted in the spring some one else had to bury them.

![]() They had beautiful burying grounds in the mountains, war in the mountains is the most beautiful of all war, and in one of them, at a place called Pocol, they buried a general who was shot through the head by a sniper. This is where those writers are mistaken who write books called Generals Die in Bed, because this general died in a trench dug in snow, high in the mountains, wearing an Alpine hat with an eagle feather in it and a hole in front you couldn't put your little finger in and a hole in back you could put your fist in, if it were a small fist and you wanted to put it there, and much blood in the snow.

They had beautiful burying grounds in the mountains, war in the mountains is the most beautiful of all war, and in one of them, at a place called Pocol, they buried a general who was shot through the head by a sniper. This is where those writers are mistaken who write books called Generals Die in Bed, because this general died in a trench dug in snow, high in the mountains, wearing an Alpine hat with an eagle feather in it and a hole in front you couldn't put your little finger in and a hole in back you could put your fist in, if it were a small fist and you wanted to put it there, and much blood in the snow.

+++

![]() Sources for this article / Bronnen voor dit artikel.

Sources for this article / Bronnen voor dit artikel.

![]() To the Frontpage of the 'Heritage of the Great War'.

To the Frontpage of the 'Heritage of the Great War'.