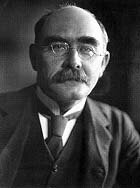

Rudyard Kipling's (picture) short story The Gardener is one of the most moving stories on the aftermath of the Great War. It is a search for a deeper understanding of the sorrow inflicted by the losses individual people suffer.

Rudyard Kipling's (picture) short story The Gardener is one of the most moving stories on the aftermath of the Great War. It is a search for a deeper understanding of the sorrow inflicted by the losses individual people suffer.

In the story Kipling uses the language of a great lie as told by a woman, Helen Turrell. She tells the lie about the birth of her 'nephew', a boy named Michael. This young man dies as an officer in The Great War. At the end of the story Helen visits his grave, somewhere in Flanders. At the cemetery a Belgian 'gardener' reveals the real identity of Michael.

The circumstances of Michael's death closely resemble those of Kipling's own only son John, who was killed in the Battle of Loos on 27 September 1915, aged 18. In a straggling attack on some houses beyond a small wood (Bois Hugo), at the farthest point of advance made by any British troops in this battle, called the Chalk Pit, Second Lieutenant John Kipling was shot in the mouth and laid in a shell-crater by a sergeant.

At the end of the Battle of Loos 20.000 British soldiers were lost, and the Kiplings received the feared War Office telegram to say that their boy was wounded and missing. Rudyard had little doubt about the meaning of this, but his wife Carrie continued to hope desperately. These were the years when he, full of guilt, wrote:

He also wrote a poem: Have You News of my Boy Jack?, that became famous. After the war Kipling visited the battlefields and wargraves in Flanders, but the author never saw his son's grave. The body of John seemed to be lost for ever. Kipling died in 1936. ( The body of his son was eventually found in 1992. It lay in the grave of an 'unknown Irish lieutenant' on plot 7 in St. Mary's Dressing Station Cemetery the Haimes, at Lone Tree, near Loos. On the grave now stands a new headstone bearing John Kipling's name. )

To France

In spring 1925 Kipling travelled France. On 14 March he visited the war cemetery in Rouen (11.000 graves) and talked to the gardeners. Returning to his hotel he wrote in a letter to his friend Rider Haggard : "One never gets over the shock of this Dead Sea of arrested corps".

That same evening he began to write what he described as "the story of Helen Turrell and her nephew and the gardener in the great 20.000 cemetery". He worked at it every evening and finished it at Lourdes on 22 March.

Obviously he took the title of his story (and his final line: supposing him to be the gardener) from the Bible. John 20:15 also identifies this Belgian gardener :

Jesus saith unto her Woman, why weepest thou? whom seekest thou? She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, Sir, if you have borne him hence, tell me where thou hast laid him, and I will take him away.

The cemetery Kipling mentions in the story, Hagenzeele Third Military Cemetery, is not a existing war cemetery.

Below follows the complete version of 'The Gardener' as it appeared in 'Debits and Credits' in 1926.

The GardenerEvery one in the village knew that Helen Turrell did her duty by all her world, and by none more honourably than by her only brother's unfortunate child. The village knew, too, that George Turrell had tried his family severely since early youth, and were not surprised to be told that, after many fresh starts given and thrown away he, an Inspector of Indian Police, had entangled himself with the daughter of a retired non-commissioned officer, and had died of a fall from a horse a few weeks before his child was born. Mercifully, George's father and mother were both dead, and though Helen, thirtyfive and independent, might well have washed her hands of the whole disgraceful affair, she most nobly took charge, though she was, at the time, under threat of lung trouble which had driven her to the south of France. She arranged for the passage of the child and a nurse from Bombay, met them at Marseilles, nursed the baby through an attack of infantile dysentery due the carelessness of the nurse, whom she had had to dismiss, and at last, thin and worn but triumphant, brought the boy late in the autumn, wholly restored, to her Hampshire home. Click here for the rest of the story Or |