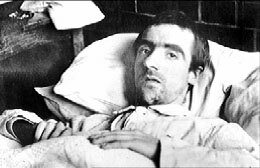

![]() A possibly shell-shocked soldier, with a "thousand yards stare"

A possibly shell-shocked soldier, with a "thousand yards stare"

(picture made in an Australian Advanced Dressing Station near Ypres)

The First World War produced an enormous and totally unforeseen epidemic of shell shock — a term that was unknown until then. In 1914 war took on a new meaning. Even far away from the trenches this war seemed to maintain absolute power over men. It was as if the war implanted an enormous destructive impulse within the soldiers’ bodies, thus destroying individual expression of will or coordinated movement.

It happened most often to soldiers who fought in the trenches of the Western Front in France and Belgium and at the Isonzo front in Italy. These were places where inhumanity, brutality and fear had become part of daily life, and where soldiers could do little else than adjust. Escape was impossible.

Military physicians did not know what to do. Many tried the new Electroconvulsive Therapy, now known as electroshock, but this did not help (it did cause brain damage and sometimes permanent loss of memory though). Afterwards we can say that only one of them, doctor William Halse Rivers Rivers (1864-1922), a British physician, seemed to understand what was really going on.

Military physicians did not know what to do. Many tried the new Electroconvulsive Therapy, now known as electroshock, but this did not help (it did cause brain damage and sometimes permanent loss of memory though). Afterwards we can say that only one of them, doctor William Halse Rivers Rivers (1864-1922), a British physician, seemed to understand what was really going on.

Rivers (picture right) maintained that these war neuroses did not result from the war experiences themselves, but were "due to the attempt to banish distressing memories from the mind". He encouraged his patients to remember, instead of trying to forget what they had been through.

His insights in psychoanalyses led the medical world into a better understanding of what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Real figures unknown

British estimates are that shell shock in the Great War affected 7-10 percent of the officers and 3-4 percent of other ranks. By 1916, over 40% of the casualties in fighting zones were victims of shell shock and by the end of the war over 80,000 cases had passed through British Army medical facilities.

The real figures however must be higher, as medical officers were told not to diagnose lower ranks as shell-shocked. Eventually the term became forbidden altogether. From June 1917 on they had to use NYD(N), short for Not Yet Diagnosed (?Nervousness).

Other terms used were neurasthenia, nerve trouble, hysteria, battle fatigue and anxiety neurosis. The Germans called it Kriegsneurose, Granatshock or Granatfieber. The French had trouble nerveux, choq de guerre, choq traumatique or traumatisme de guerre, and the Belgian soldiers suffered from d'n klop or la kloppe. The Americans called it soldier's heart and shell shock in the beginning, but later switched to neurasthenia, combat stress and combat exhaustion.

The authorities first believed that shell shock was an excuse for cowardice. Why would one man break down and become a nervous wreck, while another soldier who had the same experience remained unaffected? They felt that harsh discipline and harsh therapy would cure and prevent more cases. It did not.

The disease led to at least 200,000 discharges in the British army alone. A German military medical report talks about 613,047 cases of Kriegsneurose. In the short period the Americans fought they counted 70,000 - 100,000 soldiers with nerve problems and more than 40,000 of them had to be discharged.

Suicides and Suffering

In all armies shell shock also led to an unknown number of suicides, not to mention the innumerable soldiers who suffered the rest of their lives. In 1920 alone 50,000 British ex-soldiers were awarded a war-pension because of mental disorders.

British VAD-nurse Claire Tisdall saw them coming in from the front: "I got quite used to carrying shell-shocked patients in the ambulance. It was a horrible thing, because they sometimes used to get these attacks, rather like epileptic fits in a way. They became quite unconscious, with violent shivering and shaking, and you had to keep them from banging themselves about too much until they came round again. Of course, these were the so-called milder cases; we didn't carry the dangerous ones. They always tried to keep that away from us and they came in a separate part of the train. They'd gone right off their heads. I didn't want to see them. There was nothing you could do and they were going to a special place. They were terrible."

Another nurse, Sister Mary Stollard: "They were very pathetic, these shell-shocked boys, and a lot of them were very sensitive about the fact that they were incontinent. They'd say, "I'm terribly sorry about it, Sister, it's shaken me all over and I can't control it. Just imagine, to wet the bed at my age!'"

Another nurse, Sister Mary Stollard: "They were very pathetic, these shell-shocked boys, and a lot of them were very sensitive about the fact that they were incontinent. They'd say, "I'm terribly sorry about it, Sister, it's shaken me all over and I can't control it. Just imagine, to wet the bed at my age!'"

Sister Henrietta Hall told: "They used to tremble a great deal and it affected their speech. They stammered very badly, and they had strange ideas which you could only describe as hallucinations. They saw things that really didn't exist, and imagined all sorts of things. And, of course, they were terrified of going back."

Click here to see a a famous medical film (if your computer is configured to view quicktime movies, it is 2,5 MB) about a shell-shocked soldier, suffering from nerve deafness as it was called. The only word he can hear is bombs and when he hears it he hides under the bed.

The doctor has orders too

But almost all physicians did all they could to send these soldiers back to the mincing machine as soon as possible. They made no distinction between military and health interests. The doctor had his orders too. Shaming and the infliction of pain were the main methods they used; some doctors infected the soldiers with malaria because they thought the high fevers could heal; electric shock treatment was very popular too. The situation on the other side of the front, in Germany and in Austria, was similar.

Of course there were exceptions. Konrad Alt, a German medical officer, published an article in a leading Austrian medical journal in which he expressed great concern for the "enormous group of trembling, shaking and staggering soldiers one can frequently find walking around or sitting in wheelchairs on the streets of major cities, who are stared at everywhere, questioned, pitied and often given with presents".

They came from everywhere, but the frontlines at the Somme, Ypres, Isonzo and Verdun were incomparable. A German officer recalled from the front near Verdun:

"We saw a handful of soldiers, commanded by a Captain, slowly approaching, one at the time. The Captain asked which company we were and then all of a sudden started to cry. Did he suffer of shell shock? Then he said: 'When I saw you approach it reminded me of six days ago, when I walked this same road with approximately hundred men. And now look how few there are left...' We watched as we passed them; they were about twenty. They walked by us as living, plastered statues. Their faces stared at us like shrunken mummies, and their eyes were so immense that you could not see anything but their eyes."

Craiglockhart

In England psychiatrist William Rivers (picture right) treated shell-shocked officers at Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, in 1917. Among his patients were Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) and Wilfred Owen (1893-1918). During their stay they both wrote for The Hydra, the hospital's newspaper (click here to see a selection from The Hydra).

In England psychiatrist William Rivers (picture right) treated shell-shocked officers at Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, in 1917. Among his patients were Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) and Wilfred Owen (1893-1918). During their stay they both wrote for The Hydra, the hospital's newspaper (click here to see a selection from The Hydra).

Rivers was loved by his patients. It is interesting to note that he stuttered too, especially when speaking in public, and that he had no visual memory. He never married and he died of a sudden illness (a strangulated hernia) when he was 58 years old.

Originally Rivers was trained as a doctor. On a Cambridge University expedition to the Torres Strait, north of Australia, his psychological tests on the islanders made him realize the unexpected importance of family in their community. His field study with a hill tribe in southern India, the Todas, ultimately set the trend for anthropologists to go and visit the cultures in which they were interested, rather than staying at home theorizing.

His colleague and follower psychologist Frederic Bartlett described Rivers' character when he practiced at Craiglockhart: "Rivers was intolerant and sympathetic. He was once compared to Moses laying down the law. The comparison was an apt one, and one side of the truth. The other side of him was his sympathy. There is really no word for this. Sympathy is not good enough. It was a sort of power of getting into another man’s life and treating it as if it were his own. And yet all the time he made you feel that your life was your own to guide, and above everything else that you could if you cared make something important out of it."

On 4th December 1917 Rivers delivered a speech before the Section of Psychiatry of the Royal British Society of Medicine. In it he disclosed his revolutionary shell shock therapy: remembering instead of trying to forget. His speech was called: 'On the Repression of War Experience'. Two months later, in February 1918, his paper was published in the medical journal The Lancet.

Click here to read the complete text of his paper, taken from The Lancet.

![]() Rivers' famous paper on the repression of war experiences.

Rivers' famous paper on the repression of war experiences.

![]() If you want to read more about doctor William Rivers, his therapy, his patients and the Craiglockhart War Hospital, we advise you Pat Barker's novel trilogy Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road (Booker Prize winner 1995).

If you want to read more about doctor William Rivers, his therapy, his patients and the Craiglockhart War Hospital, we advise you Pat Barker's novel trilogy Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road (Booker Prize winner 1995).

![]() To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War

To the frontpage of The Heritage of the Great War